Valhalla

In Norse mythology, Valhalla (/vælˈhælə/ val-HAL-ə, US also /vɑːlˈhɑːlə/ vahl-HAH-lə;[1] Old Norse: Valhǫll [ˈwɑlhɒlː], lit. 'Hall of the Slain')[2] is described as a majestic hall located in Asgard and presided over by the god Odin. There were five possible realms the soul could travel to after death. First was, Fólkvangr which was ruled by the goddess Freyja. Second, was Hel, ruled by Hel, Loki's daughter. The third realm was that of the goddess Rán. The fourth realm was the Burial Mound where the dead could live, and the last realm was Valhalla, ruled by Odin and was called the Hall of Heroes.[3] The masses of those killed in combat (known as the Einherjar), along with various legendary Germanic heroes and kings, live in Valhalla until Ragnarök, when they will march out of its many doors to fight in aid of Odin against the jötnar. This eternal battle and life in Valhalla was a reflection of greater Viking ideals, for "what finer way to exist other than fighting, killing, and feasting with your erstwhile enemies, united in the common enterprise of training for the final battle”.[4] Valhalla was idealized in Viking culture and gave the Scandinavians a wide spread cultural belief that there is nothing more glorious than death in battle. The belief in a Viking paradise and eternal life in Valhalla with Odin gave the Vikings a violent edge over the other raiders of their time period.[4]

| Part of a series on |

| Utopias |

|---|

|

| Mythical and religious |

| Literature |

| Theory |

| Concepts |

| Practice |

|

Valhalla is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, in the Prose Edda (written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson), in Heimskringla (also written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson), and in stanzas of an anonymous 10th-century poem commemorating the death of Eric Bloodaxe known as Eiríksmál as compiled in Fagrskinna. Valhalla has inspired innumerable works of art, publication titles, and elements of popular culture and is synonymous with a martial (or otherwise) hall of the chosen dead. The name is rendered in modern Scandinavian languages as Valhöll in Icelandic, while the Swedish and Norwegian form is Valhall; in Faroese it is Valhøll, and in Danish it is Valhal.

Etymology

[edit]The Modern English noun Valhalla derives from Old Norse Valhǫll, a compound noun composed of two elements: the masculine noun valr 'the slain' and the feminine noun hǫll which originally referred to a rock, rocks, or mountain; not a hall, thus meaning Valhalla was originally understood as the "rock of the Slain".[3] The form "Valhalla" comes from an attempt to clarify the grammatical gender of the word. Valr has cognates in other Germanic languages such as Old English wæl 'the slain, slaughter, carnage', Old Saxon wal-dād 'murder', Old High German 'battlefield, blood bath'. All of these forms descend from the Proto-Germanic masculine noun *walaz. Among related Old Norse concepts, valr also appears as the first element of the noun valkyrja 'chooser of the slain, valkyrie'.[5]

The second element, hǫll, is a common Old Norse noun. It is cognate to Modern English hall and offers the same meaning. Both developed from Proto-Germanic *xallō or *hallō, meaning 'covered place, hall', from the Proto-Indo-European root *kol-. As philologists such as Calvert Watkins note, the same Indo-European root produced Old Norse hel, a proper noun employed for both the name of another afterlife location and a supernatural female entity as its overseer, as well as the modern English noun hell.[5] In Swedish folklore, some mountains traditionally regarded as abodes of the dead were also called Valhall. According to many researchers[who?], the hǫll element derives from hallr, "rock", and referred to an underworld, not a hall.[6]

Attestations

[edit]

Poetic Edda

[edit]Valhalla is referenced at length in the Poetic Edda poem Grímnismál, and Helgakviða Hundingsbana II, while Valhalla receives lesser direct references in stanza 32 of the Völuspá, where the god Baldr's death is referred to as the "woe of Valhalla",[7] and in stanzas 1 to 3 of Hyndluljóð, where the goddess Freyja states her intention of riding to Valhalla with Hyndla, in an effort to help Óttar, as well as in stanzas 6 through 7, where Valhalla is mentioned again during a dispute between the two.[8]

Grímnismál

[edit]In stanzas 8 to 10 of Grímnismál, the god Odin (in the guise of Grímnir) proclaims Valhalla is in the realm of Glaðsheimr. Odin describes Valhalla as shining and golden, and it "rises peacefully" as seen from afar. From Valhalla, every day Odin chooses from those killed in combat. Valhalla has spear-shafts for rafters, a roof thatched with shields, coats of mail are strewn over its benches, a wolf hangs in front of its west doors, and an eagle hovers above it.[9]

The hall is easily recognised by those who come to Óðinn:

Spear-shafts are the rafters, the hall is thatched with shields,

And the benches are strewn with byrnies.

The hall is easily recognised by those who come to Óðinn:

A warg hangs before the western door,

And an eagle hovers above . . .

Andhrímnir lets Saehrímnir, best of flesh,

Be seethed in Eldhrímnir, the cauldron,

Though few know what the Einherjar feast on.

Battle-accustomed, glorious Host-Father feeds Geri and Freki;

But weapon-stately Óðinn lives on wine alone.

Huginn and Muninn fly over the mighty earth every day;

I fear for Huginn, that he not come back,

But I look more for Muninn.

Thundr roars loudly;

Thjóðvitnir’s fish sports in the flood;

The river roars loudly,

The battle-slain think it too strong to wade.

That which stands on the holy fields,

Before the holy doors,

Is called Valgrind, the Slain-Gate;

Those gates are old,

And few know how they may be locked.

Five hundred and forty doors:

So I know to be in Valhöll;

Eight hundred Einherjar go out of one door,

When they fare to battle the Wolf.

The goat who stands on Host-Father’s hall

Is called Heiðrún,

And bites off the limbs of Laeraðr;

She shall fill a cauldron with the shining mead,

That drink will never be exhausted.

The hart who stands on Host-Father’s hall

Is called Eikthyrnir,

And bites off the limbs of Laeraðr;

And drops fall from his horns into Hvergelmir,

To which all waters wend their way.

Shaker and Mist I wish to have bear a horn to me;

Skeggjöld and Striker, Shrieker and Battle-Fetter,

Loudness and Spear-Striker, Shield-Strength and Rede-Strength,

And God-Inheritance,

They bear ale to the Einherjar.

(Grímnismál 9–10, 18–22, 23–26)

Odin, throughout this story is seen to have pet ravens that he sends out, and the warriors of his hall are dead men and ghosts who endlessly fight battles and endlessly die. There are also women who feed them and serve them alcohol and are the same spirits who chose them to die in the battles they fight. Valhalla in this story can be seen as a beautiful hall for the dead but it can also be seen as a lofty stylization of a battlefield after a fight. There are broken weapons and shields and dead bodies and ghosts cover the hall that gets ravaged by wolves and ravens. To the Vikings of the time, this was not only their desired afterlife, but a way to cope with the horrors of battle.[10]

Helgakviða Hundingsbana II

[edit]In stanza 38 of the poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana II, the hero Helgi Hundingsbane dies and goes to Valhalla. In stanza 38, Helgi's glory there is described:

So was Helgi beside the chieftains

like the bright-growing ash beside the thorn-bush

and the young stag, drenched in dew,

who surpasses all other animals

and whose horns glow against the sky itself.[11]

Prose follows after this stanza, stating a burial-mound was made for Helgi. After Helgi arrived in Valhalla, he was asked by Odin to manage things with him. In stanza 39, Helgi, now in Valhalla, has his former enemy Hunding—also in Valhalla—do menial tasks; fetching foot-baths for all of the men there, kindling fire, tying dogs, keeping watch of horses, and feeding the pigs before he can get any sleep. In stanzas 40 to 42, Helgi returns to Midgard from Valhalla with a host of men. An unnamed maid of Sigrún, Helgi's valkyrie wife, sees Helgi and his large host of men riding into the mound. The maid asks if she is experiencing a delusion, if Ragnarök is started, or if Helgi and his men were allowed to return.[11]

In the following stanzas, Helgi responds none of these things occurred, and so Sigrún's maid goes home to Sigrún. The maid tells Sigrún the burial mound is opened, and Sigrún should go to Helgi there. Helgi asked her to come and tend his wounds after they opened and are bleeding. Sigrún goes into the mound, and finds Helgi is drenched in gore, his hair is thick with frost. Filled with joy at the re-union, Sigrún kisses him before he can remove his coat of mail, and asks how she can heal him. Sigrún makes a bed there, and the two sleep together in the enclosed burial mound. Helgi awakens, stating he must "ride along the blood-red roads, to set the pale horse to tread the path of the sky," and return before the rooster Salgófnir crows. Helgi and the host of men ride away, and Sigrún and her servant go back to their house. Sigrún orders her maid to wait for him by the mound the next night, but after she arrives at dawn, she finds he is still journeying. The prose narrative at the end of the poem relates Sigrún dies of sadness, but the two are thought to be re-born as Helgi Haddingjaskati and the valkyrie Kára.[12]

Vafthrúðnismál

[edit]In the story of Vafthrúðnismál Odin disguises himself as a man named Gagnráð and visits the all knowing giant, Vafthrúðnir, to not only test his knowledge, but gain wisdom from the giant as well. Odin and Vafthrúðnir exchange questions and tests Odin on his knowledge of the afterlife and cosmology. Vafthrúðnir asks Odin about the topography of Valhalla in Stanzas 15 and 16

Vafthrúðnir said: Say this, Gagnráðr,

since you want to test your talent on the floor:

What is the river called that divides the earth

among the sons of giants and among the gods?

Óðinn said: The river is called Ífing,

which divides the earth among the sons

of giants and among the gods.

[13] Then, it is Odin's turn to ask the giant questions but instead of asking questions on the afterlife, Odin asks more esoteric questions like the fate of the gods and the end of the world. Those that are chosen to live in Valhalla with Odin prepare every day for the end of the world, also known as Ragnarök. These Vikings prepare for the battle of the end of the world everyday in the eternal battle and is the main characteristic to daily life in Valhalla.[10] Stanzas 17 & 18 of the poem describe the field in Valhalla where this battle takes place

Vafþrúðnir said:

Say this, Gagnráðr,

since you want to test your talent on the floor:

What is the field called

where Surtr and the sweet gods

will meet in battle?

Óðinn said:

The field is called Vígríðr,

where Surtr and the sweet gods

will meet in battle.

It is a hundred leagues

in every direction —

that is the field determined for them.

[13] This poem also describes the picking of slain warriors and their entrance into Valhalla in stanza 41 that states

Vafþrúðnir said:

All the unique champions

in Óðinn’s enclosed fields

fight each other every day;

they choose the slain

and ride from battle;

thereafter they sit together in peace.

The last question Odin asks, is what he himself whispered into the ear of his dying son, Baldr, at Baldr's funeral pyre. This question, revealed Odin's true identity since only he can know the answer to that question. Vafthrúðnir realizes he has been tricked, and the story concludes with the All-father, Odin, himself humbling the wise giant who must acknowledge his unparalleled wisdom.

Prose Edda

[edit]Valhalla is referenced in the Prose Edda books Gylfaginning and Skáldskaparmál.

Gylfaginning

[edit]Valhalla is first mentioned in chapter 2 of the Prose Edda book Gylfaginning, where it is described partially in euhemerized form. In the chapter, King Gylfi sets out to Asgard in the guise of an old man going by the name of Gangleri to find the source of the power of the gods.

The narrative states the Æsir prophesied his arrival and prepared grand illusions for him, so as Gangerli enters the fortress, he sees a hall of such a height, he has trouble seeing over it, and notices the roof of the hall is covered in golden shields, as if they were shingles. Snorri quotes a stanza by the skald Þjóðólfr of Hvinir (c. 900). As he continues, Gangleri sees a man in the doorway of the hall juggling short swords, and keeping seven in the air simultaneously. Among other things, the man says the hall belongs to his king, and adds he can take Gangleri to the king. Gangleri follows him, and the door closes behind him. All around him, he sees many living areas, and throngs of people, some of which are playing games, some are drinking, and others are fighting with weapons. Gangleri sees three thrones, and three figures sitting upon them: High sitting on the lowest throne, Just-As-High sitting on the next highest throne, and Third sitting on the highest. The man guiding Gangleri tells him High is the king of the hall.[14]

In chapter 20, Third states Odin mans Valhalla with the Einherjar: those killed in battle and become Odin's adopted sons.[15] In chapter 36, High states valkyries serve drinks and see to the tables in Valhalla, and Grímnismál stanzas 40 to 41 are quoted in reference to this. High continues the valkyries are sent by Odin to every battle; they choose who is to die, and determine victory.[16]

In chapter 38, Gangleri says: "You say all men who have fallen in battle from the beginning of the world are now with Odin in Valhalla. With what does he feed them? I should think the crowd there is large." High responds this is indeed true, a huge amount are already in Valhalla, but yet this amount will seem to be too few before "the wolf comes." High describes there are never too many to feed in Valhalla, for they feast from Sæhrímnir (here described as a boar), and this beast is cooked every day and is again whole every night. Grímnismál stanza 18 is recounted. Gangleri asks if Odin eats the same food as the Einherjar, and High responds Odin needs nothing to eat—Odin only consumes wine—and he gives his food to his wolves Geri and Freki. Grímnismál stanza 19 is recounted. High additionally states, at sunrise, Odin sends his ravens Huginn and Muninn from Valhalla to fly throughout the entire world, and they return in time for the first meal there.[17]

In chapter 39, Gangleri asks about the food and drinks the Einherjar consume, and asks if only water is available there. High replies of course, Valhalla has food and drinks fit for kings and jarls, for the mead consumed in Valhalla is produced from the udders of the goat Heiðrún, who in turn feeds on the leaves of the "famous tree" Læraðr. The goat produces so much mead in a day, it fills a massive vat large enough for all of the Einherjar in Valhalla to satisfy their thirst from it. High further states the stag Eikþyrnir stands atop Valhalla and chews on the branches of Læraðr. So much moisture drips from his horns, it falls down to the well Hvelgelmir, resulting in numerous rivers.[18]

In chapter 40, Gangleri muses Valhalla must be quite crowded, to which High responds Valhalla is massive and remains roomy despite the large amount of inhabitants, and then quotes Grímnismál stanza 23. In chapter 41, Gangleri says Odin seems to be quite a powerful lord, controlling quite a big army, but he wonders how the Einherjar keep busy while they are not drinking. High replies daily, after they dressed and put on their war gear, they go out to the courtyard and battle one-on-one combat for sport. Then, before mealtime, they ride home to Valhalla and drink. High quotes Vafþrúðnismál stanza 41. In chapter 42, High describes "right at the beginning, while the gods were settling", they established Asgard, then built Valhalla.[19] The death of the god Baldr is recounted in chapter 49, with the mistletoe used to kill Baldr is described as growing west of Valhalla.[20]

Skáldskaparmál

[edit]At the beginning of Skáldskaparmál, a partially euhemerized account is given of Ægir visiting the gods in Asgard and shimmering swords are brought out and used as their sole source of light as they drink. There, numerous gods feast, they have plenty of strong mead, and the hall has wall-panels covered with attractive shields.[21] This location is confirmed as Valhalla in chapter 33.[22]

In chapter 2, a quote from the anonymous 10th-century poem Eiríksmál is provided (see the Fagrskinna section below for more detail and another translation from another source):

What sort of dream is that, Odin? I dreamed I rose up before dawn to clear up Val-hall for slain people. I aroused the Einheriar, bade them get up to strew the benches, clean the beer-cups, the valkyries to serve wine for the arrival of a prince.[23]

In chapter 17 of Skáldskaparmál, the jötunn Hrungnir is in a rage and, while attempting to catch up and attack Odin on his steed Sleipnir, ends up at the doors to Valhalla. There, the Æsir invite him in for a drink. Hrungnir goes in, demands a drink, and becomes drunk and belligerent, stating that he will remove Valhalla and take it to the land of the jötunn, Jötunheimr, among various other things. Eventually, the gods tire of his boasting and invoke Thor, who arrives. Hrungnir states that he is under the Aesir's protection as a guest and therefore he can't be harmed while in Valhalla. After an exchange of words, Hrungnir challenges Thor to a duel at the location of Griotunagardar, resulting in Hrungnir's death.[24]

In chapter 34, the tree Glasir is stated as located in front of the doors of Valhalla. The tree is described as having foliage of red gold and being the most beautiful tree among both gods and men. A quote from a work by the 9th-century skald Bragi Boddason is presented that confirms the description.[25]

Heimskringla

[edit]Valhalla is mentioned in euhemerized form and as an element of remaining Norse pagan belief in Heimskringla. In chapter 8 of Ynglinga saga, the "historical" Odin is described as ordaining burial laws over his country. These laws include that all the dead are to be burned on a pyre on a burial mound with their possessions, and their ashes are to be brought out to sea or buried in the earth. The dead would then arrive in Valhalla with everything that one had on their pyre, and whatever one had hidden in the ground.[26] Valhalla is additionally referenced in the phrase "visiting Odin" in a work by the 10th-century skald Þjóðólfr of Hvinir describing that, upon his death, King Vanlandi went to Valhalla.[27]

In chapter 32 of Hákonar saga Góða, Haakon I of Norway is given a pagan burial, which is described as sending him on his way to Valhalla. Verses from Hákonarmál are then quoted in support, themselves containing references to Valhalla.[28]

Fagrskinna

[edit]In chapter 8 of Fagrskinna a prose narrative states that after the death of her husband Eric Bloodaxe, Gunnhild Mother of Kings had a poem composed about him. The composition is by an anonymous author from the 10th century and is referred to as Eiríksmál, and describes Eric Bloodaxe and five other kings arriving in Valhalla after their death. The poem begins with comments by Odin (as Old Norse Óðinn):

"What kind of a dream is it," said Óðinn,

in which just before daybreak,

I thought I cleared Valhǫll,

for coming of slain men?

I waked the Einherjar,

bade valkyries rise up,

to strew the bench,

and scour the beakers,

wine to carry,

as for a king's coming,

here to me I expect

heroes' coming from the world,

certain great ones,

so glad is my heart.[29]

The god Bragi asks where a thundering sound is coming from, and says that the benches of Valhalla are creaking—as if the god Baldr had returned to Valhalla—and that it sounds like the movement of a thousand. Odin responds that Bragi knows well that the sounds are for Eric Bloodaxe, who will soon arrive in Valhalla. Odin tells the heroes Sigmund and Sinfjötli to rise to greet Eric and invite him into the hall, if it is indeed he.[30]

Sigmund asks Odin why he would expect Eric more than any other king, to which Odin responds that Eric has reddened his gore-drenched sword with many other lands. Eric arrives, and Sigmund greets him, tells him that he is welcome to come into the hall, and asks him what other lords he has brought with him to Valhalla. Eric says that with him are five kings, that he will tell them the name of them all, and that he, himself, is the sixth.[30]

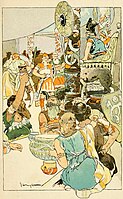

-

Gylfe Stood Boldly Before Odin (1908) by George Hand Wright

-

A depiction of valkyries encountering the god Heimdallr as they carry a dead man to Valhalla (1906) by Lorenz Frølich

Women of Valhalla and their role in the afterlife

[edit]The women of Valhalla and their role in the theology of the Norse afterlife is in stark contrast to the commonly male-dominated perceptions of Viking society, mythology, and cultural practices. Those chosen for Valhalla are often associated with heroic deeds in battle; the god Odin was said to have employed women - battle-maidens called Valkyries - to carry the dead to his hall. These Valkyries play a vital role in the functioning of Valhalla, and shape the Norse afterlife and fate of the dead. They are seen as active agents in the cosmic balance of life, death, and honor.

Valkyries are often described as "Odin's Vultures", whose purpose is to select the most glorious of men who die in battle. These Valkyries are women of violence that were seen as precursors to both honor and horror. Valkyries were physically important to the processing of men into Valhalla, which inherently entwined their fate with Viking warriors and they were heavily associated with the death of men. The Valkyries haunted their dreams and looked over the slaughter of battle, making them culturally dreaded creatures.[31] Over time, this view of Valkyries in Valhalla softened, making them into protective spirits. They are the women who serve the men of Valhalla in feasts and care for the warriors until Ragnarök. This later shift from violent overseers to sustainers of life shows how the image of women changed within Norse culture with the introduction of Christianity. [31]

Valhalla is also the only hall of the dead that is ruled by a man. all the other realms are tended to by women. Hel, the jötunn and daughter of Loki, presides over the eponymous Hel, where those who die of illness or old age dwell. Freyja, the goddess of love and war, claims half of the fallen warriors in her realm of Fólkvangr. Rán, the sea goddess, gathers the drowned into her underwater hall. These female goddesses further enforce this image of women as the overseers of death. Women in Norse Mythology then, "collect the dead, women portend death, they care for the dead and women keep the dead. In all respects except Óðin’s, it seems like an almost exclusively feminine role to keep”.[31]

Cultural Practices Resulting From the Belief in Valhalla

[edit]The belief in Valhalla influenced many cultural practices in Norse society, specifically those surrounding death and commemoration. These practices during the death and burial of a Viking reflects the society's greater understanding of honor, legacy, and the afterlife. Valhalla and the practices that occurred were deeply tied to its role in immortalizing and honoring the dead. these customs later evolved with the introduction of Christianity and created a complex tradition of the Norse afterlife.

Horse Burial: Transportation to Valhalla

[edit]Horses played a critical role in the burial and funeral processions of Viking burials. they were seen to be the dead's main transportation to Valhalla. In Egils saga Skallagrímssonar, for instance, Skallagrímr is buried with his horse, weapons, and smith’s tools, illustrating the belief in the horse’s importance for the deceased’s passage to Odin’s hall. It is also noted that Old Norse sources mention only horses, not ships, as a means to traveling to and from Valhalla.[32] This belief in horses being the main way of getting to Valhalla is also supported in the story, Sögubrot, where the character Harald Wartooth is buried with his horse and a wagon so he could ride to Valhalla.[32] The riding of a horse to Valhalla is also mention in the story, Helgakviða Hundingsbana II, where the hero Helgi rides to Valhalla after his burial and later returns on horseback to visit his living bride.[32]

Death Chants as Appeals to Valhalla

[edit]Death Chants were poetic compositions made to appease Odin and to earn a dead loved one's place in Valhalla. These death chants recorded a loved one's deed and accounted their victories to prove their worthiness to the hall of hero's.[31] The witnesses of these death chants were often daughters of the dying Vikings who acted at intermediaries by recording these poems in runes or orally. “By witnessing and recording these poems, they are in essence lending their fathers’ deaths a certain amount of weight”.[31] These rituals ensured that the deeds of the fallen would remain influential, securing their place among the honored dead in Valhalla. This also once again placed women as a central role in death and the procession of death in Viking society.

Political Continuity Through Death

[edit]The belief in Valhalla also committed to the deification of political leaders and heros. Instead of being a hall for those that died in battle, it became a symbol of honor and continuity in a heritage based society. As Gundarsson notes, “The purpose of the deification of a dead leader or hero is clear. It offers a sense of continuity,” with rulers often seated on their forebears’ burial mounds to evoke the authority of the dead.[10] As Scandinavia transitioned into a larger more unified nations, the importance of the deification of political leaders grew and Valhalla became a resting place for kings and political hero's. So, to enter Valhalla was not to achieve a "good death' but to secure a legacy among the gods and kings.

Modern influence

[edit]The concept of Valhalla continues to influence modern popular culture. Examples include the Walhalla temple built by Leo von Klenze for Ludwig I of Bavaria between 1830 and 1847 near Regensburg, Germany, and the Tresco Abbey Gardens Valhalla museum built by August Smith around 1830 to house ship figureheads from shipwrecks that occurred at the Isles of Scilly, England, near the museum.[33]

References to Valhalla appear in literature, art, and other forms of media. Examples include K. Ehrenberg's charcoal illustration Gastmahl in Walhalla (mit einziehenden Einheriern) (1880), Richard Wagner's depiction of Valhalla in his opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (1848–1874), the Munich, Germany-based Germanic Neopagan magazine Walhalla (1905–1913), the book series Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard by Rick Riordan, the comic series Valhalla (1978–2009) by Peter Madsen, and its subsequent animated film of the same name (1986).[33] Valhalla also gives its name to a thrill ride at Blackpool Pleasure Beach, UK.

Before Hunter S. Thompson became the counter-culture's Gonzo journalist, he lived in Big Sur, California, while writing his novel The Rum Diary. He wrote "Big Sur is very like Valhalla—a place that a lot of people have heard of, and that very few can tell you anything about" (Proud Highway: Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman, chapter 20).[34]

In the 2015 film Mad Max: Fury Road, the cult of the War Boys believe a heroic death in the service of dictator Immortan Joe will take them to Valhalla.[35]

A video game Assassin's Creed Valhalla was released in November 2020.[36] The video game Apex Legends features a character named Bloodhound, who often references Valhalla and the Allfather, a commonly used kenning for the Norse god Odin. Valhalla is also referenced in the manga 'Heart Gear' by Tsuyoshi Takaki as a battle ground where the 'combat' gears take turns in fighting each other to the death as their leader, Odin, observes. Another video game, Overwatch 2, features two in game cosmetic skins that were inspired by Valhalla's Valkyries. These skins are both on the flying support hero, Mercy, who heals and resurrects her team. These Valkyrie inspired skins feature a voice line where Mercy says, "till Valhalla" when she uses one of her mass team healing ability.

Elton John's first album, Empty Sky (1969), contains a song called "Valhalla".[37] Led Zeppelin's "Immigrant Song" from their third album, Led Zeppelin III (1970), contains the following Valhalla reference: "The hammer of the gods/ Will drive our ships to new lands/ To fight the horde, sing and cry/ Valhalla, I am coming".[38] Judas Priest's seventeenth studio album Redeemer of Souls released in 2014 included the song Halls of Valhalla, as lead singer Rob Halford describes as "singing about being on the North Sea and heading to Denmark or Sweden searching for Valhalla".[39] Australian band Skegss's third album, Rehearsal (2021), contains a song called "Valhalla".[40] Jethro Tull's album, Minstrel in the Gallery (1975), contains a song called "Cold Wind to Valhalla".[41]

Blind Guardian also has a song titled, "Valhalla"

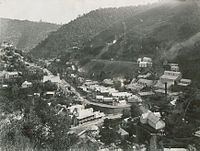

-

Walhalla, Victoria, Australia township in 1910

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Valhalla". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Orchard (1997:171–172)

- ^ a b Mark, Joshua J. "Valhalla". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2024-12-11.

- ^ a b Larrington, Carolyne (2018). "Norse Mythology and Warfare". Medieval Warfare. 8 (4): 14–18. JSTOR 48577980.

- ^ a b For analysis and discussion, see Orel (2003:256, 443) and Watkins (2000:38).

- ^ Simek (2007:347).

- ^ Larrington (1999:8).

- ^ Larrington (1999:253–254).

- ^ Larrington (1999:53).

- ^ a b c d Gundarsson, Kveldulf (2021). The Teutonic Way: Wotan; The Road to Valhalla. The Three Little Sisters.

- ^ a b Larrington (1999:139).

- ^ Larrington (1999:139–141).

- ^ a b c Pettit, Edward (2023-03-03), "Vafþrúðnismál", The Poetic Edda, Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, pp. 135–164, doi:10.11647/obp.0308.03, ISBN 978-1-80064-772-5

- ^ Byock (2005:10–11).

- ^ Byock (2005:31).

- ^ Byock (2005:44–45).

- ^ Byock (2005:46–47).

- ^ Byock (2005:48).

- ^ Byock (2005:49–50).

- ^ Byock (2005:66).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:59).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:95).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:69).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:77–78).

- ^ Faulkes (1995:96).

- ^ Hollander (2007:12).

- ^ Hollander (2007:17).

- ^ Hollander (2007:125).

- ^ Finlay (2004:58).

- ^ a b Finlay (2004:59).

- ^ a b c d e Moore, Meredith Catherine (2015). "Dread Sisterhood: Conceptions of the Feminine in Norse Depictions of Death". University of Iceland.

- ^ a b c Shenk, Peter (2002). "To Valhalla by Horseback?: Horse Burial in Scandinavia During the Viking Age". University of Oslo.

- ^ a b Simek (2007:348).

- ^ "Proud Highway: Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman, 1955–1967". readonlinefree.net. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ^ "Mad Max: Fury Road – "Shiny And Chrome" Meaning & Mythology Explained". Screen Rant.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed Valhalla". Ubisoft. 10 November 2020. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "Elton John – Empty Sky". 8 September 2022.

- ^ Morse, Tim (1998). Classic Rock Stories The Stories Behind the Greatest Songs of All Time. St. Martin's Publishing Group.

- ^ "Songfacts".

- ^ "Skegss – Rehearsal (Full Album)". YouTube.

- ^ Robinson, Thomas (2017). Popular Music Theory and Analysis A Research and Information Guide. Taylor & Francis. p. 144.

References

[edit]- Byock, Jesse (Trans.) (2006). The Prose Edda. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044755-5

- Faulkes, Anthony (Trans.) (1995). Edda. Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3

- Finlay, Alison (2004). Fagrskinna, a Catalogue of the Kings of Norway: A Translation with Introduction and Notes. Brill Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13172-8

- Hollander, M. Lee (Trans.) (2007). Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway Archived 2017-01-26 at the Wayback Machine. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-73061-8

- Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999). The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-34520-2

- Orel, Vladimir (2003). A Handbook of Germanic Etymology. Brill. ISBN 9004128751

- Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer ISBN 0-85991-513-1

- Watkins, Calvert (2000). The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-98610-9

- Welch, Chris (2005). Led Zeppelin: Dazed and Confused: The Stories Behind Every Song. Thunder's Mouth Press ISBN 978-1-56025-818-6